See-through flame protection – Article

Excellent article written by Geir Jensen who is an inventor and former fire-protection engineering consultant. He is particularly engaged in multi-discipline solutions within fire-safety communities and for the design of fire-protection products

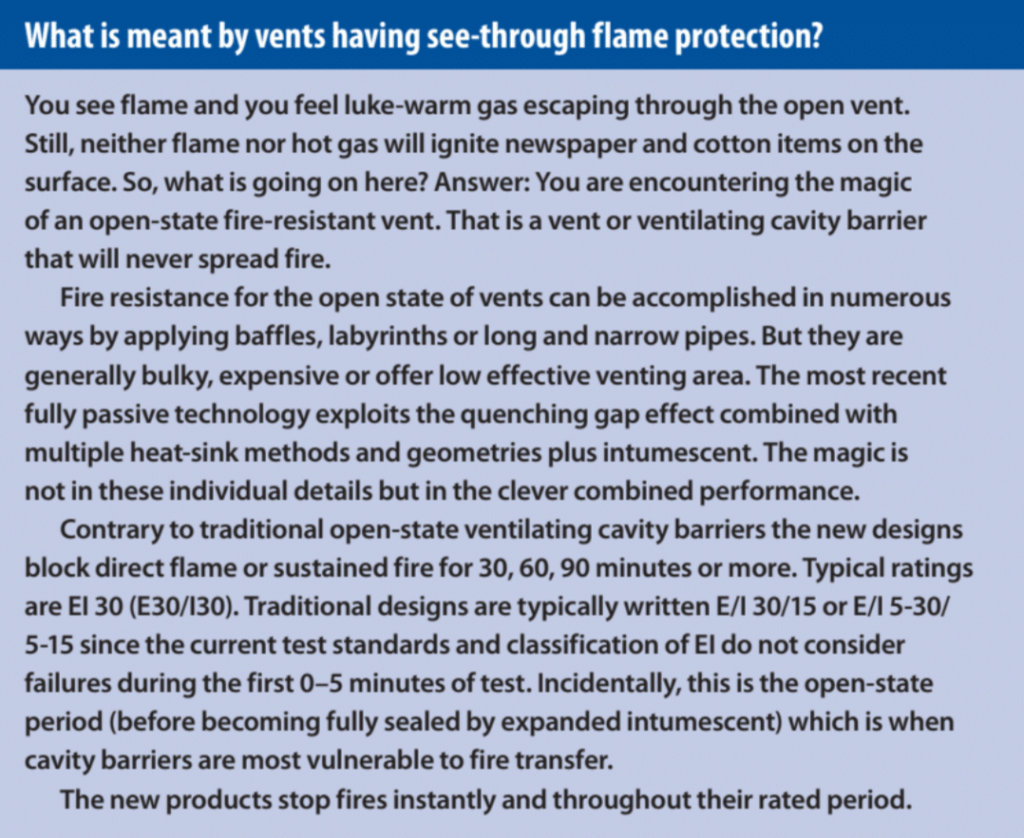

If you look up through rainscreen cladding you may see all the way up, past a number of cavity fire barriers. This see-through gap is the path of free-flowing air that keeps the cavity dry. In the case of fire, the see-through gap becomes filled with expanded intumescent material — after a while that is, after the passing of fire. Novel products now always resist fire

Do ventilating cavity barriers work as intended?

When tested with room fires that heat the air slowly and do not produce flames until 5 minutes after ignition, they work. When tested with sudden direct flaming, they certainly do not. During investigations and joint tests by the ABI and FPA following the Grenfell fire, it became apparent that something may be seriously wrong. Do they work in everyday slow fire exposures and will they fail in catastrophic fires? There are two fundamentally different types of fire-resistance-rated cavity barriers that are ventilating: the traditional design is termed ‘open’, which allows flames to pass before sealing, but more recent designs are termed ‘open state fire resistance rated’ and block flames immediately while still in the open state, before also sealing up. Sealing is typically complete between 50 seconds and 5 minutes, depending on exposure.

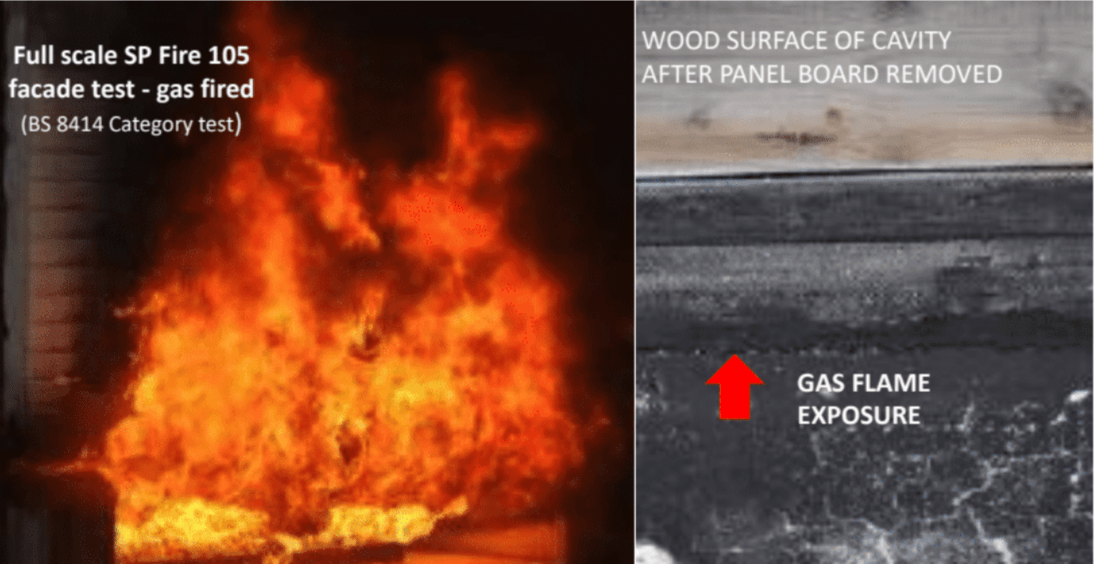

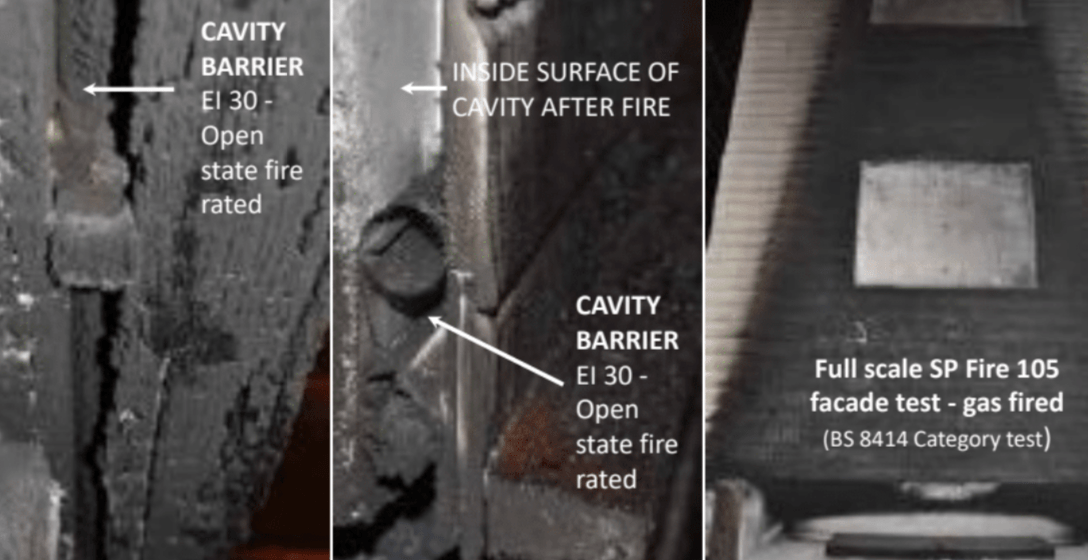

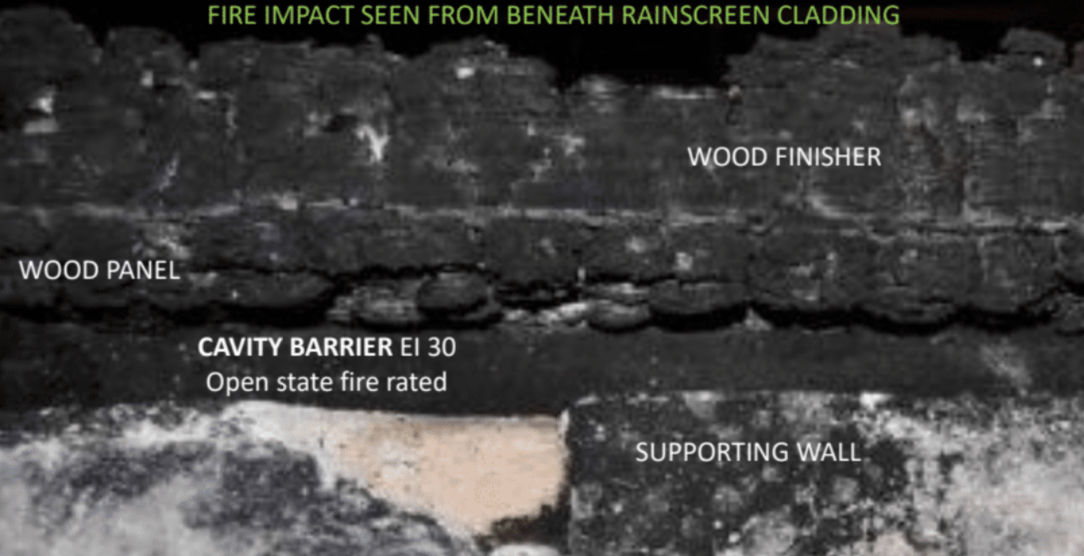

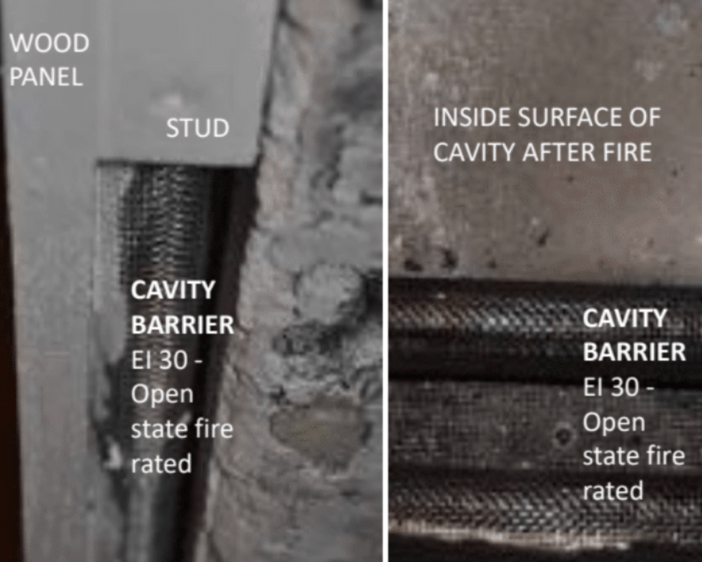

Despite 2-3 MW gas fire in full-scale test the open-state fire resistance rated cavity barriers protect wood from being ignited inside the cavity. @image courtesy of Geir Jensen

The ‘breaking of window’ fire that ignites cladding is the common scenario for facade testing. This means sudden direct flame exposure at cavity barriers may penetrate them in seconds (solid combustibles ignite at 1-3 seconds upwards). As fires escalate at great speed, such as observed at Grenfell, there is no time for the intumescent material to expand and seal. This is not a standard room fire but rather a flame attack against cavity barriers in the open state. If the combustible decor cladding at Grenfell was changed to a non- combustible variety, it still may not have prevented the furious upward spread of fire. It appears that if the most common design of ventilating cavity barriers were installed at Grenfell, they would still have failed because they were never tested by realistic fire exposure.

Test methods inadequate

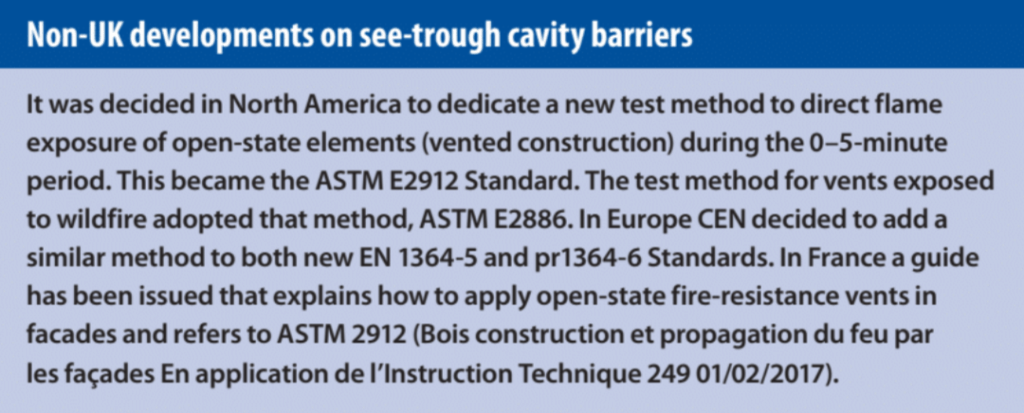

How is it possible to allow rainscreen cavity barriers to be tested using slow room (enclosure) fire furnace tests? The fire growth of those tests allows flames to pass for the first 5 minutes, and the fires are barely up to flame temperature even at 5-6 minutes after ignition. Most likely, this was accepted as the best one could do 50 years ago, and at the time open-state fire resistance against direct flame was not possible. However, recent European and US product designs have led to open- state-fire-resistance-rated cavity barriers.

That progress is recognised in fire codes and specification standards in the US and France. Since 2013, dedicated test methods and prescriptive solutions have been published. They now rely on open-state- fire-resistance-rated cavity barriers. In fact, the first product of this kind was designed and manufactured in England in 2003. It is marketed in EU mainland member states but, strangely, is yet to be sold within the UK itself.

The images above show how most recent cavity barriers perform in test. The test applied EI30 rated barriers with see-through fire protection that instantly block direct flame impingement while they are still in the open state.

Revelations in 2018

The recent joint report by the ABI, FPA 7 and RISC Authority following the Grenfell catastrophe got to grips with this. They carried out probing tests that verified the rationale of the US and French test methods and have recommended to the Grenfell Inquiry and to BSI that the full-scale test method for facades, BS 8414 be reviewed on this basis. The report further proved that compartmentation of cladding cavities is breached by common non-fire-rated wall vents and that the chimney effect of these cavities is not properly addressed by the current BS 8414.

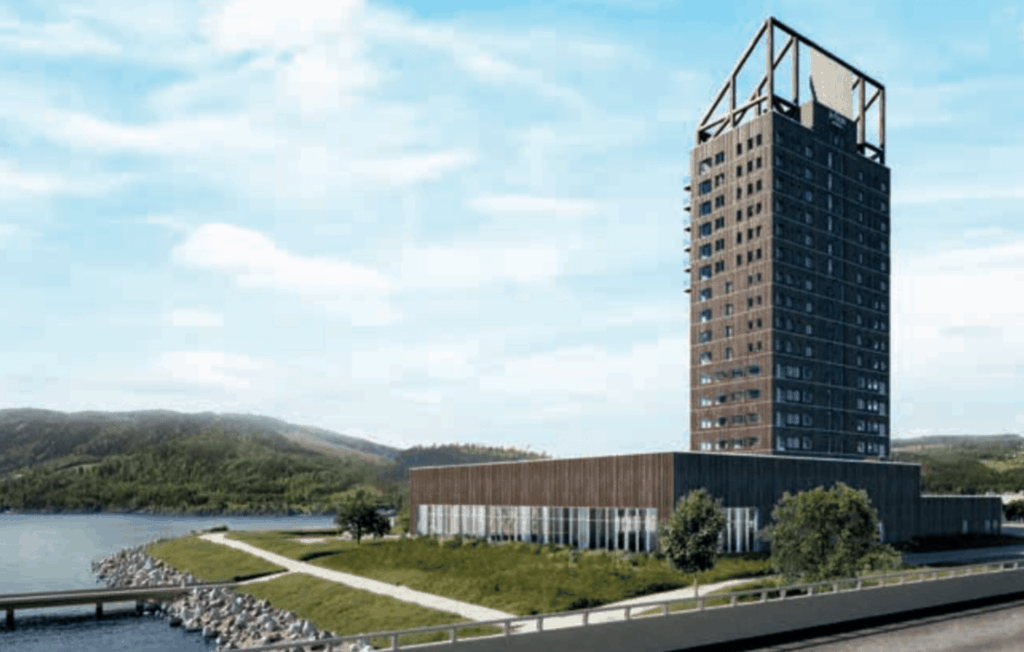

© Image courtesy of VizWork and Voll Architects

The world’s high-rise structures in wood are fire protected by vents that block flames even when flames are visible through them before they seal up. For instance the Mjos Tower, currently the world’s highest wooden residential building

All risks covered

Yet another issue with traditional ventilating cavity barriers is that they may fail when cladding moves due to wind pressure or become warped by fire. The intumescence may not expand properly to fill a gap as it widens, either due to insufficient intumescent material or because it has become brittle, loose or has dropped out. Yet another issue is wrap- around plastics, which melt, ignite and drip. This may in turn ignite other combustibles or the top plastics of cavity barriers below. In some regions, fires in attics of wooden buildings or wildfires expose wind-borne embers to other buildings that may have rain-screen cladding. Embers are also a threat as they may drop down into or be pulled up inside cavities by the chimney effect, thereby bypassing barriers unless they are ember resistant.

After decades of research and learning from real fires, all of these drawbacks of old are now mitigated. The most recent products are standing by, awaiting updates to test methods and code requirements.

Source: UK Fire Magazine